The Gambia v. Myanmar: Changing the Landscape of International Prosecution for Genocide

By Anna Henson

China. Rwanda. Bosnia. Darfur. Cambodia. These are just some of the most infamous post-World War II genocides.[1] The United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) defines “genocide” as including the following five categories of actions against national, racial, ethnic, or religious groups: (1) killing of a group’s members, (2) infliction of mass injuries and/or mental harm, (3) creating conditions calculated to bring physical destruction, (4) measures preventing a group’s births, and (5) forcible transfer of children to another group.[2] These actions are at risk of happening across the globe–daily.[3] Why, then, have only three genocides–Rwanda, Bosnia, and Cambodia–been legally recognized and tried?[4] To answer this question, we must look to the process and jurisdiction of the current international courts.

International Court System

There are two international courts, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).[5] The ICJ was created as an organ of the United Nations (UN) in October of 1945, months after the UN itself was founded.[6] The ICJ may preside over two types of cases: “legal disputes between States submitted to it by them (contentious cases) and requests for advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by UN organs and specialized agencies (advisory proceedings).”[7] Parties to contentious cases may only include states that have accepted the ICJ’s jurisdiction in one or more of the following ways: (1) entering into a special agreement to submit the dispute to the Court, (2) a jurisdictional clause (e.g., typically in treaties), or (3) through the reciprocal effect of declarations made by them under the Statute of the Court where each has assented to the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[8] Advisory proceedings are only open to the five organs of the UN and 16 specialized agencies of the UN family or affiliated organizations.[9]

In 1948, the UN passed the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the CPPCG.[10] It was at this time that the UN recognized the need for a permanent international court to deal with the atrocities of the genocides that had happened.[11] In response, the UN developed an ad hoc tribunal for each situation; however, the ad hoc tribunals were established within the framework of the UN to deal with specific situations and thus have a limited mandate jurisdiction.[12] In 1998 the ICC was established in order to be able to try individuals for crimes without the need for a special mandate from the UN.[13] The ICC “tries individuals charges with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression.”[14] To be clear, the ICC does not replace national criminal justice systems.[15] The ICC investigates and prosecutes individuals only if the State (which must be party to the Rome Statute[16]) concerned does not, cannot, or is unwilling to do so genuinely.[17] The ICC may exercise this jurisdiction when the crime was committed in the territory of a States Party or if the perpetrator was a national of a State Party.[18] In sum, the most fundamental differences between the courts is that the ICJ an organ of the UN and tries states whereas the ICC is not an office or agency of the UN and tries individuals.

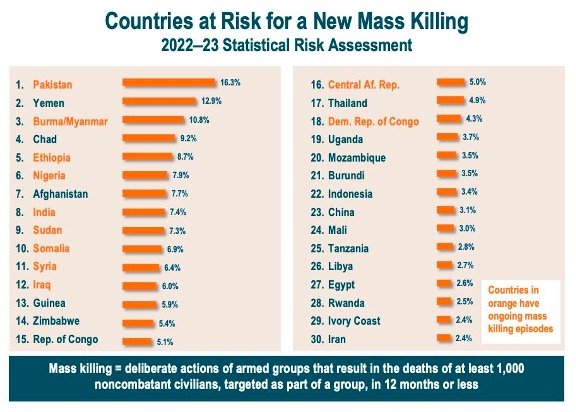

Countries at Risk for Mass Killing 2022-2023: New Early Warning Report, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Nov. 29, 2022), https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/blog/countries-at-risk-for-mass-killing-2022-23 (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

It’s the jurisdictional reach of these courts and the permitted parties that have allowed many genocide cases to fall through the cracks–that is, until The Gambia v. Myanmar.[19] The Gambia v. Myanmar is a historic case for a number of reasons; the Gambia is the first country to submit a case to the ICJ against another country that is not in the same continent, and that is not directly affected by the actions of the country they are bringing the case against.[20] What’s even more remarkable is that the ICJ accepted the case.[21]

The Gambia v. Myanmar

In their application, The Gambia alleges that Myanmar has “breached and continues to breach its obligations under the Genocide Convention through acts adopted, taken and condoned by its Government against the members of the Rohingya group.”[22] Myanmar posed several preliminary objections to The Gambia’s submission.[23] First, Myanmar argued that the ICJ lacks jurisdiction, or alternatively, that the application is inadmissible because the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, not The Gambia, is the “real applicant.”[24] Second, Myanmar asserts that The Gambia lacks standing to bring this case.[25] Third, Myanmar argues that the ICJ lacks jurisdiction or that the application is inadmissible since The Gambia cannot validly seise the Court in light of Myanmar’s reservation to Article VIII of the Genocide Convention.[26] Fourth, Myanmar contends that the ICJ lacks jurisdiction, or alternatively that the application is inadmissible, because there was no disputes between the parties under the Genocide Convention on the date of filing of the application.[27]

The Gambia’s Justice Minister, Abubacarr Tambadou, presented the case against Myanmar in the International Court of Justice. Courtesy Wiki Images.

The ICJ rejected all four of Myanmar’s preliminary objections.[28] In response to the first preliminary objection, the ICJ held that a State’s acceptance of a proposal from an intergovernmental organization of which it is a member to bring a case before the ICJ does not detract from the status as the applicant before the Court.[29] Motivation is not relevant for establishing jurisdiction.[30] Regarding the second preliminary objection, the ICJ concluded that The Gambia, as a State party to the Genocide Convention, had standing to “invoke the responsibility of Myanmar for the alleged breaches of its obligations” because the State parties to the Genocide Convention “have a common interest to ensure the prevention, suppression and punishment of genocide by committing themselves to fulfilling the obligations contained in the Convention.”[31] In other words, all Contracting Parties have a common interest in compliance with the obligations under the Genocide Convention, which is owed erga omnes partes, or “toward all parties”; therefore, a breach of those obligations injures all Contracting Parties to the Convention.[32]

Addressing the third preliminary objection, the ICJ held that Article VIII[33] does not pertain to the seisin of the ICJ because the function of “competent organs” within the meaning of the provision is different from the ICJ, “whose function is to decide in accordance with international law such disputes as are submitted to it.”[34] Finally, regarding the fourth preliminary objection, the ICJ held that the conduct of the parties as well as statements and documents exchanged between the parties was sufficient to establish that there is a “dispute relating to the interpretation, application and fulfilment of the Genocide Convention existed between the Parties at the time of the filing of the application by The Gambia.”[35]

Looking Forward

The fight against genocide is far from over. Not only does The Gambia v. Myanmar now proceed to the merits of the central genocide case, but it is unclear what types of remedies the ICJ will provide should The Gambia win or how this will impact future cases.[36] While the ICJ has taken a liberal approach to the issues of jurisdiction, it is unclear whether the approach of the ICJ on a different kind of erga omnes right will remain as broad or whether this case leaves the door open for a state to bring suit for victims who are not its nationals.[37] However, considering how many countries are already at risk for new mass killing in 2023, the potential for taking action against the countries perpetuating these atrocities is worth the fight.[38]

[1] Timeline of 20th & 21st Century Events Associated with Genocide, Colorado Department of Education, https://www.cde.state.co.us/cosocialstudies/holocaustandgenocideeducation-timeline (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[2] Id.

[3] Countries at Risk for Mass Killing 2022-2023: New Early Warning Report, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Nov. 29, 2022), https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/blog/countries-at-risk-for-mass-killing-2022-23 (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[4] Rachael Burns, Genocide: 70 Years On, Three Reasons Why The UN Convention Is Still Failing, The Conversation (Dec. 18, 2018), https://theconversation.com/genocide-70-years-on-three-reasons-why-the- un-convention-is-still-failing-108706 (last visited Jan. 21, 2023). See also, Human Rights Watch, Some Common Misconceptions About The ICC, PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pa ges/frontline/shows/karadzic/genocide/iccmisp.html (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[5] This does not address other methods of dispute resolution, such as arbitration, tribunals, or special courts, as these organizations do not address genocide. To learn more about these organizations, visit https://www.justice.gov/jmd/ls/international-courts.

[6] History, International Court of Justice, https://www.icj-cij.org/en/history (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[7] How The Court Works, International Court of Justice, https://www.icj-cij.org/en/how-the-court-works (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[8] Id.

[9] Id.; The five organs permitted to request advisory proceedings are the General Assembly, Security Council, Economic and Social Council, Trusteeship Council, and the Interim Committee of the General Assembly. Organs and Agencies Authorized to Request Advisory Opinions, International Court of Justice, https://www.icj-cij.org/en/organs-agencies-authorized (last visited Feb. 4, 2023).

[10] Timeline of 20th & 21st Century Events Associated with Genocide, supra note 1.

[11] Understanding The International Criminal Court, International Criminal Court, 9 (2020), https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/Publications/understanding-the-icc.pdf (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[12] Id. at 9-10.

[13] Id. at 10.

[14] Id. at 10.

[15] Id. at 11.

[16] The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is a treaty adopted during a conference of 160 States on July 17, 1998 that established the first treaty-based permanent intentional court. The Rome Statute establishes the crimes falling within the jurisdiction of the ICC, the rules of procedure and mechanisms for cooperation as well. Countries that have accepted these rules are known as States Parties. Id. at 10.

[17] Id. at 11.

[18] Id.

[19] The Gambia Brings Historic Genocide Case Against Myanmar, International Bar Association (2019), https://www.ibanet.org/article/02A82017-63C8-4C20-A9EB-BC9DBFCF26BC (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[20] Id.

[21] Md. Rizwanul Islam, The Gambia v. Myanmar: An Analysis of the ICJ’s Decision on Jurisdiction Under the Genocide Convention, American Society of International Law (Sep. 21, 2022) https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/26/issue/9 (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[22] Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (The Gambia v. Myanmar), Judgment, 2022 I.C.J. 7, 16 (July 22), https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/178/178-20220722-JUD-01-00-EN.pdf.

[23] Md. Rizwanul Islam, supra note 21.

[24] Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, supra note 22.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Id. at 38-39.

[29] Id. at 19.

[30] Id. at 20.

[31] Id. at 36-38.

[32] Id. at 34.

[33] The portion of Article VIII in question here says, “Any Contracting Party may call upon the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III.” Myanmar’s ratification contained the following reservation: “With reference to Article VIII, the Union of Burma makes the reservation that the said Article shall not apply to the Union.” Id. at 29.

[34] Id. at 31-32.

[35] Id. at 29.

[36] Helen Regan, Myanmar Ordered to Prevent Genocide Against Rohingya by Top UN Court, CNN (Jan. 23, 2020), https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/23/asia/icj-myanmar-genocide-ruling-intl-hnk/index.html (last visited Jan. 21, 2023).

[37] Md. Rizwanul Islam, supra note 21.

[38] Countries at Risk for Mass Killing 2022-2023: New Early Warning Report, supra note 3.